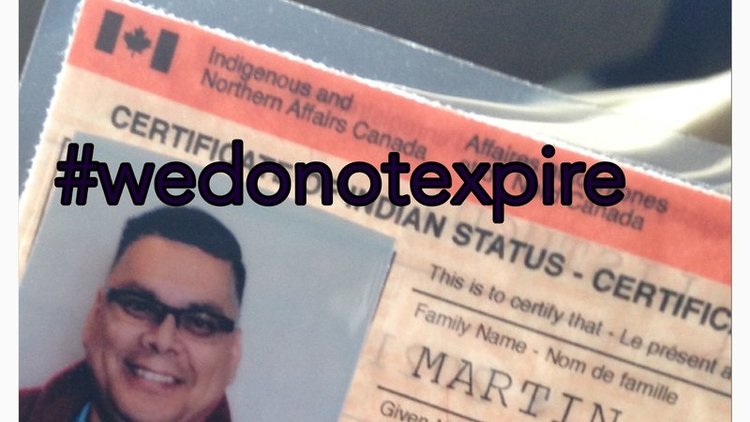

An online petition is calling on the federal government to scrap the renewal process for Indian Status cards.

“The renewal process is too lengthy and unnecessary and un-accommodating,” says Edward Martin’s petition on Change.org. After two months, the petition has collected more than 6,200 signatures.

A status card is government ID that gives “registered Indians” access to some benefits, such as tax exemption for certain purchases made on-reserve and for the PST segment of the HST in Ontario.

“Imagine having to renew your SIN number,” Martin said in an email to The Huffington Post Canada. “It’s the same thing.”

Originally from the Listuguj Mi’gmaq First Nation on the Quebec-New Brunswick border, Martin was in the middle of moving to Victoria, B.C. in August when his status expired.

Two months earlier, he drove more than 350 kilometres from North Bay, Ont. to Gatineau, Que. to renew his status card at the Indigenous and Northern Affairs office. When he got there, Martin said he was told he needed to provide a passport photo, scan of his birth certificate, and a declaration signed by a lawyer to prove his identity.

“I was upset and realized something needs to be done,” he said. “The renewal process is just another attempt to keep us jumping through hoops.”

The requirement to renew status cards “is consistent with other official identification documents, such as passports and drivers licenses,” according to the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada website. Renewal can be done in person or by mail, but the applicant must pay for all document printing and mailing costs.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada did not respond to HuffPost Canada’s request for comment about Martin’s petition.

“Imagine having to renew your SIN number … It’s the same thing.”

“The status card is NOT a passport,” Martin wrote in his petition. A person’s registration number never changes, so to renew it is “redundant,” he told HuffPost.

The federal government started defining who is legally “Indian” with the Indian Act in 1876. At the time, anyone who went to university would lose their status, as would any woman who married a non-status person.

‘A form of apartheid law’

“The Assembly of First Nations, as well as other leaders and academics, have described the Indian Act as a form of apartheid law,” according to the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Foundations website.

The concept is based on the assumption that indigenous people are “‘children’ requiring control and direction to bring them into more ‘civilized’ colonial ways of life,” it explains.

In 1969, then prime minister Pierre Trudeau tried to abolish the Indian Act and dismantle the Department of Indian Affairs.

While many indigenous people agreed that the act was problematic, the move wasn’t supported. The policy was “overwhelmingly rejected” by indigenous people who said that assimilating into mainstream society would not create meaningful equality.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.